You know how it feels to finally have a conclusion of value that feels good, looks reasonable, and fits the narrative you have written. This explains how the business has grown in the face of economic and industry challenges. There is no better feeling in all of the business valuations! (Except for maybe receiving that final payment for the report.) But, that’s not what I want to discuss today. Today is the day I address one of the least talked about aspects of business valuation. The final value conclusion and how it becomes final.

As appraisers, we deal with stacks of raw data, financial information, comparative industry data, economic forecasts, expectations in marketing, personnel requirements, modifications in rent expenses, variations in risk, and even more esoteric events that might affect our final value conclusion. We accumulate all this information, and in the process of analyzing it all, draw our conclusions about what it all means and illustrate those conclusions throughout our analyses. Then, when we finally feel we have a grasp on it all, we apply various methods under the three approaches; Asset, Income, and Market, and we move to complete our reconciliation and…

*gasp*

There (can be / and sometimes are) wide variations in the various indications of values presented!

I know this is an issue we have all seen and have chosen how to deal with it in our own ways, but here is how I want to address it in this posting.

We know that each method under each approach looks at the overall value of the subject business from a different point of view, and each method relies on different data and assumptions to get there, right? As such, it is not unheard of for an appraiser to miss something in the first go. When I get to this point, I begin to ask myself questions about the underlying data, to see if I may have misapplied an adjustment in either the determination of the applicable income stream (Did I use the wrong income stream?) or if the risk rate I used was off.

Lately, I have been hired to appraise some businesses that just do not quite fit into any specific industry, so I have been having to look at “similar” businesses, but I know they have a significant difference from my subject.

For example, I recently appraised a business that hauled only a specific type of freight, for basically only one customer. The closest market data I could find was for general freight haulers, short distances. (Yes, I am being vague and slightly changing the market description. Confidentiality issues need to be protected.) The subject was paid fees based on a series of contracts, which may or may not be renewed at the end of each contract’s expiration period. There was no expectation of continued calls from various customers calling for different freight to be hauled to different locations.

When those contracts ended, the business was done, therefore I decided that there was no terminal value, especially since those same contracts stated that they could not be sold. How comparable to the subject do you think the market data I had access to was? Could I rely on that data to reliably illustrate a conclusion of value? Based on the facts of that case, I decided I could not, which was a big relief to me as the indications of value provided under the price to revenues and price to pre-tax net income multiple methods I used, were quite a bit larger than the value I believed was most accurate.

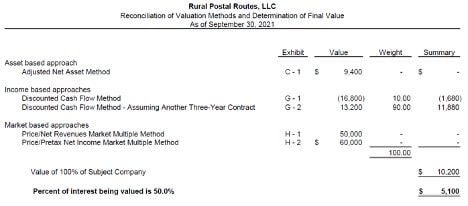

Just for fun, here is a screenshot of the reconciliation from that report. I’ve changed the name of the business, but its name should provide a hint as to the nature of the freight it hauled.

Now, since you don’t have a copy of this report, you can’t see all the descriptions and explanations I wrote throughout the report, foreshadowing the discussion I summarized above. However, if you just looked at this chart, with no context, you would wonder why those market approach methods were given no weight at all. In fact, you might even accuse the appraiser (me) of ignoring the higher indications of value in order to drive the concluded value down for the benefit of the husband, as this is for a divorce case.

Just looking at this chart, you can’t see the hours I poured into trying to figure out why those methods’ indications of value came in so much higher. You can’t see the experimentation, the modifications, the changing assumptions, everything else I tried to make sense of the results the numbers was showing me. Sometimes, the methods don’t all come in together in a nice, neat, and tight grouping, but it doesn’t have to be because we got something wrong. In this case, I believe I did everything correctly, it’s just that the data I used, was simply not similar enough to justify placing any weight on it. (It took me way too long to figure that out, by the way.)

This is the secret I alluded to above. Business appraisers are generally just as surprised as everyone else by their final numbers. There are almost always extra sessions where the appraiser is reviewing their work and attempting to understand why the numbers are coming out the way they are. Generally speaking, methods under the three approaches, at least those methods that also include the intangible assets held by the business, arrive at different indications of value that fall within a few percentage points of each other.

I have seen other business appraisers who simply decide that all the methods are always equally reliable and applicable and finish their conclusion of value by assigning at least some weight to each method used, including the adjusted net asset value method which, by itself, does NOT measure any intangible value. I do tend to have a problem with that basic assumption. As an appraiser, we need to keep the following quote from Revenue Ruling 59-60, Sec. 3.01 (emphasis added) in mind throughout our process:

A determination of fair market value, being a question of fact, will depend upon the circumstances in each case. No formula can be devised that will be generally applicable to the multitude of different valuation issues arising in estate and gift tax cases.

Often, an appraiser will find wide differences of opinion as to the fair market value of a particular stock. In resolving such differences, he should maintain a reasonable attitude in recognition of the fact that valuation is not an exact science. A sound valuation will be based upon all the relevant facts, but the elements of common sense, informed judgment, and reasonableness must enter into the process of weighing those facts and determining their aggregate significance.

Every method relies on different data, and our analysis of that data may be the only thing that separates the applicable data from the unreasonable. I can’t stress enough the importance of the report’s narrative aspects. We have to explain our thought process to the reader, because without that explanation, businesses may be over-or under-valued, and that does not serve our clients, nor the profession as a whole.

I do enjoy getting paid to deliver my opinion, but I enjoy it even more when that opinion is well supported, and I am very comfortable with the available data and its relationship with the subject!

If you have any specific questions you’d like to see addressed, or even better, if you have any specific questions you have already answered and would like to share those answers in a short article format that I can publish in next month’s newsletter, please let me know. Otherwise, I’ll see you all next month!

Recommended Courses

ISBA Learning: Looking for authoritative business appraisal courses, tools, webinars, and more? Stop trying to create resources from scratch and start taking advantage of having exactly what you need right at your fingertips in ISBA Learning.